Welcome to the first part of our Chronology of Chesterfield’s History.

On this page we set-out the early history of Chesterfield – up to 1599. You’ll find our other chronology pages accessible via the links below.

We comprehensively revised this page in July 2023 and are working on the others to present something like an authoritative and concise history of the town.

Click on the links below to take you to our other chronology sections:

- To the introduction

- 2 – 1600 to 1799 (This section was last revised in March 2023 – but we are working on a completely new revision to be published in the future)

- 3 – 1800 to 1899 (This section was last revised in March 2023. We are are working on a completely new revision to be published in the future)

- 4 – 1900 to 1999 (This section was last revised in March 2023. We are are working on a completely new revision to be published in the future)

- 5 – 2000 onwards. (This section is not substantially populated. At some stage in the future we hope to add more recent events from the year 2000 onwards, but we do not currently have work in progress on this).

Sources used in compiling our chronology are listed in the introduction.

Chesterfield and District Local History Society would particularly like to thank Philip Cousins, Janet Murphy and Philip Riden for assistance with this section of our chronicle.

Chronology of Chesterfield’s history 1: Prehistory to 1599

This page covers the period in Chesterfield’s history from prehistoric times until the late 16th century.

We know least about the prehistoric and Roman periods, and to some extent Anglo-Saxon periods in the town’s history. Onwards from the Domesday Survey of 1086 Chesterfield’s history is now fairly well worked out, certainly compared to some towns of a similar size, especially in the north of England.

During the period covered in this section the town grew from a Roman fort into a busy market town, with a large new (from around 1189-1199) market place.

Governance wise the latter period marked a move from the lord of the manor to what might be considered a relatively modern corporation, particularly after the granting of the town’s royal charter in 1598. The church was established and remained an important influence and indeed property owner in the area and surrounding chapelries.

Set out below is a selective narrative with, perhaps, the arbitrary cut-off date of 1599.

Anyone who is more interested in the history of the town and its growth in the period covered in this part of our chronology is particularly recommended to consult the following:

JM Bestall, History of Chesterfield, volume I Early and Medieval Chesterfield (1974).

Philip Riden, History of Chesterfield, volume II part I – Tudor and Stuart Chesterfield (1984).

Philip Riden and John Blair, History of Chesterfield, volume V – Records of the borough of Chesterfield and related documents 1204-1835 (1980).

Philip Riden and Chris Leteve, Chesterfield streets and houses (2019).

PRE-HISTORY As much of the Chesterfield region is highly urbanised, with a history of industrial development, there is little in the way of recorded pre-historic occupation.

Traces of Mesolithic occupation on the site of the Ibis Hotel (Lordsmill Street) were identified. A few flint tools were also discovered in the rampart fill of the Roman forts in the town. Additionally, two bronzes from the Middle Bronze Age have been recorded, of undetermined provenance, in the Chesterfield coal measures.

Possibly Anglo-Saxon pottery has also been found in archaeological excavations, but archaeologists from the University of Manchester have concluded that an Anglo-Saxon presence in the town has not been proved or disproved.

ROMAN

Note on Chesterfield’s Roman fort from Chesterfield Streets and Houses by Philip Riden and Chris Leteve (2019):

‘During the conquest of Britain in the 1st century AD, a small fort was built near the edge of a spur of high ground over-looking the Rother valley immediately to the north of the point at which the river was joined by the Hipper. The fort was one of two built on the Roman road between the larger forts at Derby (Derventio), 25 miles to the south, and Templeborough, near Rotherham, 12 miles to the north, to guard a section of the Roman road known since the 14th century as Ryknield Street as it ran through Derbyshire and south Yorkshire. The other smaller fort was at Coneygrey Farm, between Pentrich and Oakerthorpe, midway between Chesterfield and Derby. The course of the Roman road from Derby to Rotherham has never been established for certain beyond the point where it crossed Mill Lane (in Wingerworth), about three miles south of Chesterfield.’

For a useful discussion about Roman Chesterfield see also Mark Patterson’s book Roman Derbyshire (2016) pp. 219-249.

70s First Roman fort thought to have been built (in the early Flavian period).

EARLY 100s The first fort may have contracted in size during the Hadrian period.

The road serving the fort and guarded by it is the so-called Ryknield Street. This, it is thought, passes through the fort ‒ its route is represented by Tapton Lane and St Mary’s Gate.

MID 100s Increased military activity ‒ the fort is augmented during the Hadrian period. Subsequently, during the second century, the fort in Chesterfield possibly closed, with the ramparts and defensive ditches levelled.

It is possible that some form of Romano-British presence on the fort’s site was maintained into the fourth century. The civilian settlement just outside the fort may have been continually occupied during this period and beyond. If it was wholly abandoned new settlers recognised the site of the fort, reoccupied it and named their settlement after it.

6TH OR 7TH CENTURIES Probable construction of a mother church for north east Derbyshire – within (probably in one corner) the site of the former Roman fort.

955 King Eadred, in the Burton Abbey Charter, grants Chesterfield to one of his followers – Uhtred Child. This is the only pre-Norman conquest mention of the town. The extent of the estate is not specified.

1037 The date sometimes given for the erection of a church in the town – but there is no documentary evidence for this.

1086 Chesterfield is part of the Manor of Newbold. In the Domesday survey. The name ‘Newbold’ is probably used, as a new build was being undertaken at this time near the site of the present Eyre Chapel. The whole estate is possibly administered from a building at or near the now demolished Manor Farm.

At this time the manor comprised a large estate, a manorial centre and a ring of ‘berewicks’ around it. These Newbold berewicks were Whittington, Brimington, Tapton, Chesterfield, Boythorpe and Eckington. (The latter is not the present Eckington, but is a lost hamlet probably in Newbold township). The entire population has been estimated at no more than 90.

There was ‘sokeland’ attached to the manor in 1086. This is land occupied by free peasants who owed suit of court (attendance at the manor court) to Newbold but nothing more. Their presence helps to explain why in some of the townships there is a good deal of freehold land in later centuries.

Parts of the manor of Chesterfield were granted by the King to William Peverel sometime after 1086 – but not Chesterfield itself.

1093 Chesterfield, a manor in its own right, is named in a writ (not a charter). This gives the church of Chesterfield and the chapels in the bailiwicks (the area of jurisdiction of the manor) to the dean of Lincoln and his successors. This made the dean the lay rector of Chesterfield and so he received most of the income from the land belonging to the church and chapels. Because of the size of the church estate in Chesterfield it became known as a ‘rectory manor’. The writ does not confirm the existence of a pre-Conquest church in Chesterfield.

1154 Henry II got back those bits of the manor which had been granted to William Peveril the elder, after his son William Peveril the younger was attainted and his lands forfeit for rebellion at the start of the reign. (Being ‘Attainted’ arose after being guilty of a serious capital crime such felony or treason).

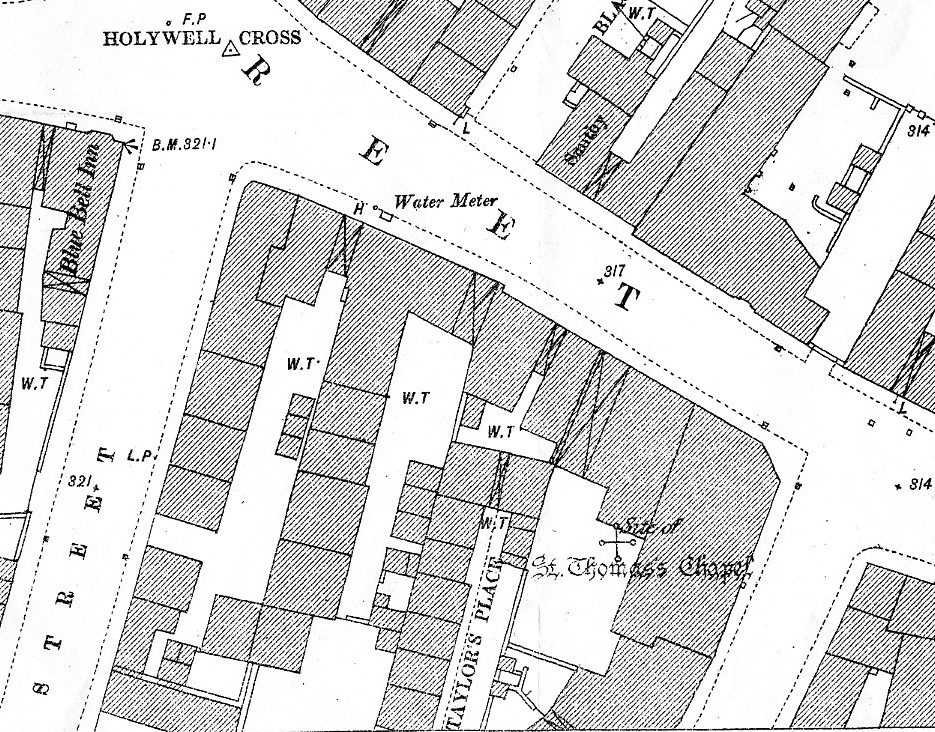

1165 The Sherriff’s annual returns in the Pipe Rolls begin to record fees from Chesterfield market. The market area would have been just to the north and by the parish church (on or near the northern end of St. Mary’s Gate and Holywell Street) – not the present Market Place. (The pipe rolls were maintained by the Exchequer and record accounts of debts and payments).

1169 Money levied towards the cost of the marriage of King Henry II’s son has the burgesses of Derby contributing £20, Nottingham £26.13s.6d and Chesterfield’s men contributing £5 – perhaps indicating the relative importance of the town.

1182 The ‘Pipe Rolls’ record that Chesterfield had a fair.

1189-1199 At some time during this period a New Market (as it became known) is laid out by the Crown officials, who were in charge of the manor, on the site now occupied by the Market Place and New Square. The Shambles is also laid out. It does not grow out of temporary structures but has permanent buildings on it from the start. As part of this new development burgage plots were laid out. These had frontages to the Market Place with long plots of land behind them.

The Old Market did not go out of use immediately and may have been used for smaller markets at least for a time. This radical extension of the town effectively doubles the built-up area. (For a brief history of Chesterfield’s markets see the Derbyshire Victoria County History Trust’s blog here.)

The timber framed part of the ‘Royal Oak’ public house dates from the 16th century and was heavily restored around 1900. It was certainly not a rest-house for The Knights Templar during the Crusades, as local ‘legend’ has it. The original public house was the building adjoining to the south; before being joined to it the timber framed house was, at one time, divided into two butchers’ shops. (Philip Cousins).

1195 A rent-charge out of the manor of Chesterfield assigned to the brethren of the Hospital of St. Leonard, indicates the founding of the former leper hospital at Spital (from where the place-name originates).

1199 Chesterfield mentioned as a borough in the Pipe Rolls – five years before the charter of 1204.

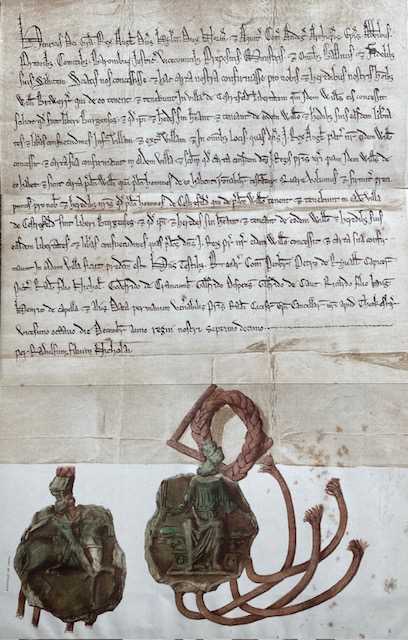

1204 King John gave the manor of Chesterfield, Brimington and Whittington to William Brewer, with two weekly markets (Tuesday and Saturday), and a fair for eight days, at the festival of the Holy-Cross (14 September). This grant makes Chesterfield a borough but does not incorporate the burgesses as the 1598 charter (see below) does. They hold their privileges from the lord of the manor, which makes it a ‘seigneurial’ borough.

1209-22 Around this time the name ‘Bishop’s Mill’ (corn milling, etc) is named (in Latin). This is despite it being the property of the dean of Lincoln. The mill was situated on the river Rother, near Piccadilly Road. It, or a successor building, was still extant in 1857 – but it has been demolished for many years.

1219 The Gild of the Blessed Mary established. Its affairs are both religious and to uphold the town’s liberties.

1224 Licence granted by the dean of Lincoln for a chantry in the chapel at Walton confirms that a chapel building is at that place by this date.

1230s Separate manors had been established by this period in Newbold, Boythorpe, Brimington, Whittington and Tapton.

By the 1230s Newbold (like some others) was a manor independent of Chesterfield. The manor of Newbold was probably administered from a property nearby – marked by Manor Farm which was demolished some years to be replaced by a Roman Catholic Church – itself now closed. (The late A Jackson).

1232 (December 28) Henry III confirmed the charter granted by John to the burgesses of Chesterfield. The burgesses were tenants of the Lord of the manor and were not free of control from the former.

1233 Hugh Wake becomes Lord of the Manor of Chesterfield. This followed the death of William Brewer (the younger) and division of his estate between coheiresses.

1234 Incorrectly said to be the date that the tower pillars and east end of the present parish church are dedicated. This is a misreading of a charter of that date, which simply mentions (but not does give a date for) the anniversary of the church’s consecration.

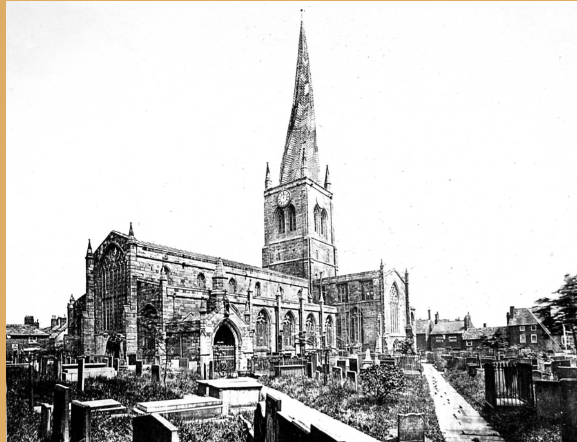

The majority of the present church building dates from the 13th and 14th centuries – representing a rebuilding of what was once a Norman structure. The church building is added to thereafter – it eventually becomes the largest parish church in the county. Before and after this date land is being added to the church estate.

There are separate medieval chapels at Whittington, Brimington, Wingerworth, Walton, Brampton and Newbold. Whittington becomes more or less a separate parish. Wingerworth and Brampton remain parochial chapelries within Chesterfield parish. The position of Brimington is less clear. Walton may have been a private chapel for the Bretons but given the distance to the parish church it would probably also be used by local residents. The same was true of St Martin’s, Newbold, but there is no clear statement of its position before the Reformation. The Eyre chapel building at Newbold appears not to have been used as a parochial chapel serving inhabitants.

1266 The inhabitants of Brampton claimed a part of the burial-ground of Chesterfield church as their own, and were to repair the walls of that part at their own expense.

1266 The Battle of Chesterfield occurs, a relatively small skirmish in and about the town. This was part of an eradication of baronial opposition of those resisting Henry III, following the Battle of Evesham. Robert Ferrers, Earl of Derby; Baldwin Wake, Lord of the Manor of Chesterfield, and John d’Ayville were leaders of the defeated barons. The royalist forces were led by Henry of Almain, nephew to Henry III. Wake escaped the fighting to the Isle of Axholme, where he joined other barons. Wake’s property was later restored to him.

1266 Leland, writing in the first half of the 16th century, has a Robert de Ferrers taken prisoner at the ‘castrum de Chestrefelde’. This is assumed to be Tapton Castle – a scheduled ancient monument – now represented by an inconspicuous mound backing on to a wall opposite the main entrance to Tapton House. In fact, it may not be a castle at all but a fortified early medieval homestead. Dr Pegge (see 1704) supposed that this was the site for the Roman fort – an incorrect theory often repeated until the fort was discovered in the town centre in the 1970s.

1290 in the early autumn, King Edward I visits the area, including Chesterfield.

1291 Chesterfield church with its two chapelries is valued at the relatively high level of £80. Only the very large parish of Bakewell, its chapelries and extensive lands, is valued higher in the county at £194.

1294 John Wake, Lord of Liddel and Chesterfield confirms the liberties and free customs hereto granted in charters of 1204 and 1233 and others. This confirms Chesterfield’s position as the main administrative and trading centre of the north-eastern part of Derbyshire – a position that it would have held for some time.

It is thought that woollen cloth, linen making (hosiers and weavers) and leather trades, especially tanning, were important industries in Chesterfield at this time. Lead from the Peak District would also have been traded in the town. The area’s iron industry (bloomeries at Barlow) is first mentioned in a Louth abbey charter of the 12th century.

The Gild of the Holy Cross is one of the gilds active in the medieval period. The Gild of the Blessed Mary is much older. These gilds (or guilds), which might also include craft gilds or social gilds, were entitled to various privileges laid down in the 1294 charter. Most established chapels in the parish church.

As John Bestall comments in his History of Chesterfield, volume I; ‘By the end of the thirteenth century, in the years following the grant of the Wake charter of 1294, Chesterfield had come to possess virtually all the institutions that were to shape its life during the Middle Ages’.

1330 Thomas Wake, then Lord of the Manor claims the right to hold a second fair in the town. Included is the mention of a toll being levied on merchants with iron forges.

1348/9 The Black Death. The impact in Chesterfield is not known but some years later, in 1365, a shortage of chaplains is reported due to its effect.

1349 Thomas Wake dies without issue – his sister Margaret is heir, but dies only a few months after her brother. Her heir is daughter Joan (later Holland)

1351 John, second son of Edmund of Woodstock, is Lord of the manor of Chesterfield. He is the second husband of Joan. (The Manorial descent is somewhat complicated by Joan’s marriages during the period and will not be recorded fully here. Those interested are referred to John Bestall’s History of Chesterfield, volume I.)

1350 Believed that the present parish church tower and spire were probably completed by this date. The dean of Lincoln is rector.

1357 Chantry of St. Michael (within the parish church) founded by Roger de Chesterfield.

1361 – Though it would have been established earlier, the Chapel of St Helen is mentioned in a deed, when rent is granted to it from a tenement in the town. This chapel was in the Holywell Street/Sheffield Road area.

1400 Joan the widowed countess of Kent, petitions the crown for the restitution of her husband’s Chesterfield property. A commission of inquiry finds it has no net value per year, but does have an annual value of just over £55.

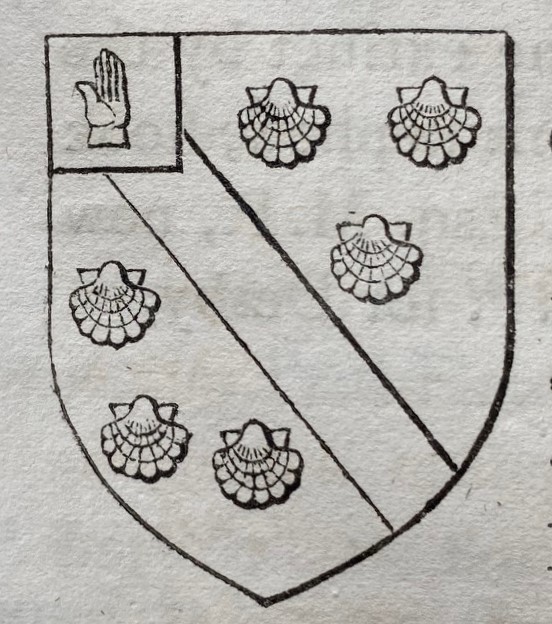

FIFTEENTH AND SIXTEENTH CENTURIES The Foljambe family have considerable influence over the Chesterfield area, through their land-holdings, wealth and personal influence. Their rivals during this period were the Pierreponts of Nottinghamshire and principally the Leakes, who had a house at Sutton. The Frechvilles held Staveley but appear to have had little or no interest in Chesterfield.

As Philip Riden has set-out in volume II, part I of the History of Chesterfield ‘Much of Chesterfield was either held by religious houses (including the manors of Newbold, Dunston, Holme, Normanton and part of Brampton), or manorial rights had become divided as in Hasland and Boythorpe. The typical landowner was a minor gentry family with a small estate centred on a single house…’

Successive Lords of the Manor never lived in the borough. Consequently there is no manor house within the town.

1422 (1 January) Thomas Foljambe of Walton, Richard Foljambe of Bonsall and Thomas Cokke of Bakewell head an assault by 200 Lancastrian supporters on a service at the parish church.

1430 Rood screen erected in the parish church.

1442 Death of Joan Holland (see 1349) of Bourne (Lincolnshire), Duchess of Kent. Richard Neville, Earl of Salisbury, is Lord of the manor of Chesterfield ‒ a relation to Joan.

1446 Chantry chapel dedicated to St Mary established on the bridge at the river Hipper at what is now Lordsmill Street. Founded by Richard Neville, Earl of Salisbury, who is then lord of the manor.

1460s Chesterfield recorded in the top ten of towns receiving woad (a blue dye) through Southampton. This probably indicates the town’s importance in wool and linen production.

1465-6 A now lost deed refers to a chapel to St Thomas for the first time, though its origin is much earlier. The chapel is thought to have been at the Holywell Street end of what was then Knifesmithgate (now Stephenson Place – covered by the closed Eyre’s store). It was demolished in the 1830s.

1480 A formal statement on the customs and governance of the borough is agreed by the burgesses of Chesterfield. This includes a provision for burgesses to elect an alderman and council to govern the borough. This is a major step towards establishment of a modern borough. In the same year a renewed statement is issued by King Edward IV confirming the ancient privileges enjoyed by tenants in Chesterfield and neighbourhood. The 1480 composition is one of the framed and glazed ‘charters’ in the council’s possession.

At this time the administration of local justice remained with the crown. Public health and nuisance issues were in the hands of the manor court leet.

1483 Supposed to have been a brass foundry in the town by this date. There is additionally the Heathcote family of bell founders in the town who appear to have cast bells in the period, starting with Ralph (d. 1502. Their foundry was situated in the area now occupied by the car park at the junction of Holywell Street and Saltergate.

1500s Around this time the parish church south transept was raised with clerestory (vertical windows) added.

1500 The only medieval domestic building to have survived into the present – the former Peacock Inn, Low Pavement – is built around this date for the Revell family of Carnfield Hall, near Alfreton. Two of the three original bays survive and were restored in the 1980s.

1507 Hospital of St. Leonard granted by Henry VII., to John Blythe; but seized by Margaret, Countess of Salisbury, as an appendage to the manor of Chesterfield.

1510 Henry Foljambe interred in Chesterfield parish church – the first member of the important Chesterfield family to be interred in the part of the church now known as the ‘Foljambe Tombs’. He had died in 1504. The last family member to be interred there was Godfrey in 1595. The Foljambe monuments have been gathered together in modern times in the Lesser Lady Chapel. It is not clear where they were originally, although there may have been a ‘Foljambe Quire’ in the pre-Scott Victorian restored church.

1509-1547 West end of Chesterfield church rebuilt during this period.

1531 Exchange of estate between the Countess of Salisbury and the Earl of Shrewsbury – the latter becomes lord of the manor.

1547 Ford’s history of the town (published ion 1839) states ‘Chesterfield parish contained about 2,000 persons of sixteen years of age’.

1549 Having merged shortly before this date, the gilds of the Blessed Virgin Mary and of the Holy Cross are dissolved. James Hardwick of Hardwick is granted a lease of their property for 21 years. Their chapels and altars in the parish church remain.

1558 A member of a leading Chesterfield family – Ralph Clarke – petitions the Crown regarding the loss of income that the burgesses had incurred following the dissolution of 1549. A new lease is granted to Clarke for 99 years.

1558 (November 17) Commencement of the earliest existing register at the parish church of Chesterfield.

1560 By this date the town is partly enclosed by Tapton, Brimington, Whittington, Newbold and Boythorpe. All were described in the Domesday survey as berewicks and by this time are separate manors. Completing the circle are Brampton and Walton, already separate manors at the time of Domesday, plus a later creation – Hasland.

The ecclesiastical parish of Chesterfield has the above settlements as chapelries, plus Calow and Normanton. Also included are Brampton, Whittington and Wingerworth which have chapelry buildings.

Unsurprisingly, over the centuries, this building has been a focal point for the town and surrounding areas. As might be expected it has seen many changes, including removal of the gravestones, which significantly altered its setting after work had been undertaken in c.1932 to c.1935.

As covered in this section of our chronology the building’s site probably occupies a corner of the Roman fort(s). The dates of 1037 or 1093, sometimes ascribed as its foundation, are not correct. Neither is that of 1234, which has been incorrectly said to be the date that the tower pillars and east end of the present parish church are dedicated.

1560 Death of the 5th Earl of Shrewsbury. Succeeded by George Talbot, who takes a much greater interest in his Chesterfield manorial estate than his father.

1562 The 6th Earl of Shrewsbury’s survey of his property – ‘The Grand Inquest’ – is part of his efforts to maximise income from his Chesterfield estate and heralds an era of conflict with the town’s burgesses. It also refers to a newly built hall in the Market Place.

1566 (October) A new document prepared by the burgesses includes powers to make by-laws. This and other noted measures effectively turns them into a corporation-like body. Shortly after, the burgesses decide to seek confirmation of their royal charter.

1566 (December) Chancery issue patents to the burgesses, one confirming renewal of the 1232 charter. Now described as ‘free burgesses of the town’ this is an important upgrade from the earlier ‘men of the town of Chesterfield’ statement. Other issued patents recognise Wake’s 1294 charter, the statement of 1480 and 1566.

1567 (January) Shrewsbury summons burgesses to Sheffield to a heated meeting at which he issues threats to them over their recent moves designed to strengthen their hand in the town’s affairs.

1568 Shrewsbury acts to reject the claims made by the burgesses. This effectively ended any hopes of Chesterfield receiving a royal charter and of the burgesses extending their self-governance powers.

1580s The burgesses make renewed efforts to confirm their powers, which are again resisted by the Earl of Shrewsbury.

(From 1568 until 1584 the earl has custody of Mary Queen of Scots. It is thought that she spent one night at the Foljambe’s house at Walton Hall during a move from Sheffield to Tutbury in 1569. Bess of Hardwick (Shrewsbury’s wife at the time), may never have met her and the Queen certainly never went anywhere near Hardwick, as some Victorian antiquaries claimed).

1585 Sir Godfrey Foljambe of Walton dies, leaving a benefaction to create a new grammar school in the town, a charity and money for a preacher to assist the vicar. Though somewhat suppressed by the activities of the 6th Earl of Shrewsbury, the Foljambes were probably regarded as the single most dominant family in Chesterfield, but their influence tails off considerably after Godfrey’s death.

1586-7 The first great plague in Chesterfield.

1587 Charles Robinson (who died of the plague) leaves £5 to the town for the establishment of a grammar school.

1590 Death of the 6th Earl of Shrewsbury and of burgess Nicholas Clarke – chief proponents of disagreements between the Lord of the Manor and the burgesses.

1595 Godfrey Foljambe (b.1558 and son of Sir Godfrey – see above 1585) dies. He had never administered his father’s will. He is the last of the family interred in the impressive collection of family tombs in the parish church (see 1510). The Foljambes are in a period of rapid decline in the town, from which they never recover.

1598 (April) The crown grants a charter of incorporation to the burgesses. The preamble cites the earlier grants of 1204 and 1232. Corporation given the style ‘The mayor, aldermen and burgesses of the borough of Chesterfield’. Six aldermen are appointed, six brethren and twelve capital burgess – a total corporate body of 25, including the mayor. The charter gives the corporation powers to have a council house, what is effectively a town clerk, make bylaws, hold meetings, etc. and defines how elections are to be held. Ralph Clarke is nominated the first mayor of Chesterfield. The 1598 grant also gives the corporation the power to administer the grammar school, which is why there was no separate body of governors until 1837.

1598 Around this year, the new Chesterfield Grammar School opens on land part of and adjacent to St Helen’s chapel, which is appropriated for its use. The charter of 1598 has given the burgesses powers to create the grammar school.

Click here to access the next part of our chronology.

LINKS TO OTHER CHRONOLOGY PAGES

This page was revised on 25 July 2023 when we added an illustration supplementing information on two of Chesterfield’s wayside chapels, but due to technical issues this was removed on 24 June 2024.